Howard Nightingale Strople was born at North Intervale, Guysborough County, on July 4, 1887, to James Robert and Mary Eliza (Lipsett) Strople. James was the son of William and Hannah Strople, Intervale, while Mary Eliza was the daughter of John and Mary Lipsett, Clam Harbour. The couple married at Manchester, Guysborough County, on September 28, 1875, and raised a family of 14 children—nine sons and five daughters—in their North Intervale home.

| ||

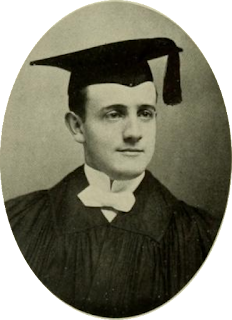

| Howard Nightingale Strople (c. 1900) | |

At age 18, Howard left home for the United States, crossing the border at Rumford Falls, near Vanceboro, Maine, on August 5, 1905, on his way to Boston, Massachusetts. By 1910, he was working as an “electric lineman” while residing in a Mattapan boarding house. On April 15 of that year, Howard completed a “Declaration of Intention,” an official application for American citizenship.

On September 21, 1914, Howard married Laura E. Stanley, daughter of Henry Stanley and Emeline Adams, at Newburyport, MA. Laura, a Quebec native and “shoe worker,” was living in Reading, MA, at the time of the marriage. The couple established residence in Reading, where their first child—a daughter, Mabel Edith Strople—was born on June 23, 1916.

It appears that Howard’s occupation as a lineman occasionally took him far from home. In October 1916, for example, he crossed the American border at St. Albans, Vermont, on his way home from Biggar, Saskatchewan. The following year, available documents indicate that the Strople family returned to Canada and established residence in Montreal.

|

| Howard and his younger brother Guy (c. 1914) |

The family’s relocation may have been prompted by the United States’ April 6, 1917 declaration of war on Germany, which led to the introduction of a military draft. On June 14, 1917, Howard enlisted with the 2nd Reinforcing Company, 5th Royal Highlanders of Canada, at Montreal. He spent four months in uniform before he was discharged as “medically unfit” due to “flat feet” on October 19, 1917. A note in Howard’s service file provided further details:

“Left foot is quite flat. Arch is completely broken down. Man suffers pain in left leg. Right foot is partially flat and man suffers some pain in his right leg after marching. Man has had to be taken off P. T. [Physical Training] exercises on account of his feet being so painful.”

Several weeks before his discharge, Howard and Laura’s infant daughter Mabel Edith died at Montreal, QC, on October 2, 1917, and was laid to rest in Cimetière Mont Royal, Outremont, QC.

Two of Howard’s brothers also enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the First World War. An older sibling, Chester Alvin Strople (DOB December 28, 1885), also spent time in the United States prior to the war. Chester returned to Canada in October 1912, crossing the border from South Dakota to Fort Frances, Ontario. The brothers may have been in touch with one another after Howard’s enlistment, as Chester attested for service with the same unit—2nd Reinforcing Company, 5th Royal Highlanders of Canada—on August 6, 1917.

On October 3, 1917, Chester was transferred to the 1st Depot Battalion, 1st Quebec Regiment, one of numerous similar units established across the country following the introduction of conscription in Canada. A combination of age and health issues meant that Chester remained in Canada for the duration of his time in uniform.

Promoted to the rank of Corporal on July 22, 1918, he was diagnosed with a “hernia” on December 9, 1918, and discharged from military service nine days later. A note in his service file states that Chester suffered from a “reducible left hernia” prior to enlistment and there was “no aggravation due to service.”

On April 30, 1919, Chester married Elodia Sybil Stanley—possibly a relative of Howard’s wife Laura—at Montreal, QC. Chester was working as a shoemaker at the time of the ceremony. The couple settled at Mercier, QC, where Chester passed away in 1960.

Whitfield Raymond Strople, a younger brother of Howard and Chester, also enlisted during the First World War. Born on September 26, 1895, Whitfield left Nova Scotia in March 1915 for the United States, where he joined his oldest brother Ralph, who was residing at Cambridge, MA.

Whitfield was likely motivated to enlist by the military draft implemented in the United States. Many Canadians living there at the time preferred to serve with the Canadian Expeditionary Force and made their way back to Canada to enlist. While Whitfield completed a draft registration card at Cambridge, MA, shortly afterward he travelled by train to Fredericton, NB, where he attested with the 236th Battalion (New Brunswick Kilties) on July 3, 1917.

Whitfield’s age made overseas service much more likely than his older brothers. On October 30, 1917, he departed for the United Kingdom with the 236th and disembarked on November 19. When the 236th was dissolved in early 1918, Whitfield was transferred to the 1st Canadian Reserve Battalion, Seaford. One week later, he was assigned to the 72nd Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada), a unit that was recruited by the same Montreal regiment his older brothers had joined.

On the same day as his transfer, Whitfield crossed the English Channel to France. He joined the 72nd in the field on March 23, 1918. Exactly two months later, he was admitted to No. 13 Canadian Field Ambulance, having been exposed to poison gas from an artillery shell. On July 25, Whitfield was admitted to No. 14 General Hospital, Wimereux. Five days later, he was discharged to a Convalescent Depot, where he remained for a month.

Whitfield reported to the Canadian Infantry Base Depot on September 2, 1918, but did not return to the forward area until after the November 11, 1918 Armistice. On May 4, 1919, he crossed the English Channel to the United Kingdom and departed for Canada aboard SS Adriatic on July 8, 1919. One week later, Whitfield was discharged from military service at Halifax, NS.

While Whitfield appears to have returned home to North Intervale after his discharge—his British War and Victory medals were delivered to that address in March 1922—he eventually returned to the Boston area, where he worked as a “servant” in the household of Herbert Nelson, Sharon, MA. Other documents indicate that he spent time in Seattle, WA, as well.

Whitfield Strople passed away at Montreal, QC, on May 4, 1929. While genealogical sources claim that he died “from the effects of poison gas,” the information in his service file suggests that his exposure was mild. He spent only five days in hospital and no after-effects were detected in a medical examination prior to his discharge. There is no documentary evidence in his file to support a conclusion that his death was connected to his overseas service.

Some time after his military discharge, Howard and Laura Strople returned to the United States. The 1920 census for Manchester, New Hampshire, completed on January 5, 1920, lists Howard Strople, age 31, as a boarder in the household of Mary Adams, a 61-year-old nurse. Howard’s occupation is listed as “electrician at box factory.” Also in the home are his wife Laura, age 28, and a daughter Doris Florence, age four months.

The family remained in the United States for a short period before returning to Guysborough County. At the time of the June 1, 1921 Canadian census, Howard, Laura and Doris were living with Howard’s parents, James and Mary. Some time afterward, the family travelled to Ontario, where Howard obtained employment as a lineman with the Toronto Hydro-Electric Company.

|

| Howard (back) with children Bud (left), Gus, Phil & Doris (May 1931) |

In the ensuing years, at least four sons—Philip (c. 1923), William Augusta "Gus" (c. 1929), John Allen (November 27, 1935) and Howard "Bud" (year of birth unknown)—joined the Strople family. Despite his age and family obligations, a year and a half after the outbreak of the Second World War, Howard decided to enlist with the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals (RCCS) at Toronto on April 30, 1941.

Considering his age—Howard was 54 years old at the time—overseas service was out of the question. However, his skills as a lineman proved useful to the RCCS’s home defense efforts. Two weeks after his enlistment, Howard was transferred to Fortress Signal Company, Atlantic Command, Halifax, where he completed a training program. On June 1, he was awarded trades pay as a “Lineman’s Helper, Group C.”

During the war, No. 6 Fortress Signal Company assisted with the defence of Halifax and its eastern approaches. One of several similar units established across the country, its personnel were responsible for erecting and maintaining communication systems—telephone and/or telegraph lines—required by units conducting home defence operations. The Atlantic Command focused on strategic locations along Canada’s east coast.

On September 1, 1942, Howard was transferred to No. 1 Company, Atlantic Canada Signals. Two months later, he was promoted to the rank of Lance Corporal and awarded trades pay for “B Lineman.” Howard remained with No. 1 Company throughout the winter and spring of 1941-42. On July 1, 1942, he was attached to the Headquarters Gaspé Defences for pay and assigned to AA [Anti-Aircraft] Battery, Burnside, Dartmouth, NS.

At the beginning of the war, Canada’s meagre anti-aircraft defences consisted of eight four-inch guns. Military authorities initially focused on key ports along the Atlantic coast—Halifax and Sydney, NS, and Saint John NB—distributing the limited resources available to these three locations as protection from a possible German naval attack.

Halifax was second only to Liverpool, England, in the volume of Allied supplies that passed through its port. The Bedford Basin provided an important convoy assembly area. The harbour also contained an Imperial Oil refinery, established in 1918, a large ammunition magazine, a naval dockyard and troop transport berth facilities.

The strategic value of these resources prompted military authorities to locate two anti-aircraft guns at York Redoubt to guard the harbour entrance. In late August 1939—only days prior to Canada’s official declaration of war on Nazi Germany—No. 4 AA Battery arrived at Halifax from Kingston, ON, with four three-inch anti-aircraft guns. Two were deployed at the Imperial oil facility, while the other two were deployed at Burnside to protect the magazine.

In early 1940, four modern 3.7-inch anti-aircraft guns arrived from Britain. Three were assigned to the Burnside battery, while a fourth was placed at Hartlen Point, across from Devil’s Island, for training purposes. Despite the increase in the number of guns, the Fortress Commander in charge of the area’s defences noted a significant shortage in personnel required to operate and maintain these facilities.

Arrangements were later made for the guns of British naval vessels docked in the harbour for refitting and the AA armament of other naval units in port to be placed under the tactical control of the Fortress Commander. Telephone communications were established from the GOR [Gun Operational Room] at the Halifax Citadel to the various berths where naval vessels were docked, and all AA guns on board were manned for emergency use.

While this system was already in place at the time of Howard’s arrival in Halifax, communication lines between Fortress Command, the dockyards and AA batteries no doubt required regular maintenance and repair, a task that was assigned to Royal Canadian Corps of Signals personnel. During the time Howard spent in the Halifax area, he no doubt was part of these efforts.

On October 19, 1942, having spent almost 18 months in Halifax, Howard was attached “for all purpose” to Arvida Defences, Quebec. Located 240 kilometres north of Quebec City, near the banks of the Saguenay River between Chicoutimi and Jonquière, the “industrial city” of Arvida had been established in 1927 by the Aluminum Company of Canada (Alcoa) as the site for its first aluminum smelter.

An abundant supply of hydro-electricity from nearby power plants at Isle Maligne, Chute-à-Caron and Shipshaw provided the smelter with the resources required to process South American bauxite into aluminum. The plant’s location close to the Saguenay River, a tributary of the St. Lawrence, provided water access for importing the required raw materials and exporting finished products to market.

During the Second World War, the operation became the Western world’s largest aluminum production facility. Such a valuable resource was a tempting target during wartime. Military authorities feared possible sabotage of the local power grid, an aerial attack on the plant, or a submarine attack on the nearby Port Alfred facility.

In response, a detachment of the Chaudière Regiment was stationed in the area in June 1940 and assigned the task of defending the smelter, dams and power plants. When the unit headed overseas, a Company of the Veterans Home Guard took their place. Military authorities, however, were concerned with defending the location from possible sabotage attack.

In response, on June 11, 1941, four three-inch guns previously located in Halifax were re-assigned to the Arvida area. No. 14 AA Battery, which had provided the required manpower in Nova Scotia, accompanied them to their new home. One section of two guns protected the Isle Maligne power plant, while the other two were positioned west of the Arvida plant.

In January 1942, No. 17 AA Battery, a newly-formed French-speaking unit, assumed responsibility for the anti-aircraft guns in the Arvida area. Three months later, eight new 40 mm guns were deployed in the area, in addition to the four older weapons. The commencement of the “Battle of the St. Lawrence”—a German U-boat campaign that resulted in the loss of 23 vessels from May 1942 to November 1944—further heightened concerns of a possible attack on the facility.

One week after his October 19, 1942, transfer to Arvida Defences, Howard was granted a 14-day furlough and quite likely returned home to Toronto for a visit. During that time, he was promoted to the rank of Acting Corporal with pay on November 1. Three and a half weeks later, he was attached to No. 17 AA Battery, Isle Maligne.

Howard’s time in the Arvida area was brief. On December 4, 1942, he was admitted to St. Vallier Hospital, Chicoutimi, were he was diagnosed with stomach cancer. Medical staff soon determined that, due to his illness, he was “unable to meet the required military physical standards,” due to his illness. Discharged from hospital on December 21, he was granted a five-day special leave of absence on Boxing Day and once again likely returned home to Toronto.

On January 3, 1943, Howard proceeded to Quebec, where he was once again admitted to hospital. At month’s end, he was officially “struck off strength” by RCCS and assigned to No. 5 District Depot, Quebec. Howard was formally discharged from military service on March 17 and returned to his home at 553 Dufferin St., Toronto.

|

| Cpl. Howard Strople's grave marker, Prospect Cemetery, Toronto, ON |