Douglas Seaman Cameron was born at Aspen, Guysborough County, on June 18, 1917, the oldest of George Leibert and Alma (McKeen) Cameron’s five children. Douglas was a direct descendant of Dougal Alistair Cameron, born at Kilmallie, Argyllshire, Scotland, on June 18, 1786. Dougal immigrated to Nova Scotia between 1825 and 1835, and was head of one of Cameron Settlement’s founding families.

|

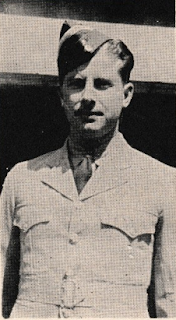

| Flight Sergeant Douglas Seaman Cameron |

Among Dougal’s children was a son, John Dougal “Short John,” born at Fort William, Lochaber, Scotland, in 1827 or 1828. John Dougal accompanied his father to Nova Scotia. At the time of the 1871 Canadian census, he was residing at Caledonia, Guysborough County. Later records identify his place of residence at Forks of St. Marys. John Dougal passed away at Aspen in 1892, and was laid to rest in Evergreen Cemetery.

John Dougal’s son, Dougal/Dougald Archibald “Archie,” was born at Caledonia or Aspen on October 15, 1864. Archie married Margaret Isabelle “Maggie” McDonald, daughter of Hugh and Catherine McDonald, Lochaber, on June 11, 1894. Archie and Maggie’s oldest child, George Leibert, was born at Aspen, Guysborough County, the following year.

On October 27, 1916, Leibert married Alma Margaret McKeen, daughter of Samuel and Eliza McKeen, Aspen. While Alma’s family also traces its roots to the British Isles, her ancestors followed a much longer and different route before arriving in Nova Scotia. The family’s North American pioneer, John McKeen, was born at Londonderry, Ireland, in December 1700 and immigrated to the American colonies with his family, arriving at Boston Massachusetts, on August 4, 1718.

Around 1741, John married Martha Cargill at East Darby, New Hampshire. The couple eventually settled close to the mouth of the Connecticut River—across Long Island Sound from Long Island, New York—where four of the couple’s five children were born. John established a shipping and supply company that operated routes to Boston, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and St. John, New Brunswick.

In 1760, the family relocated to Truro, where they were among the community’s earliest settlers. John and two of his sons—William and John Jr.—were also “grantees” of the township established there, receiving adjoining lots. At the time, the community consisted of 60 families. John Sr. and his wife Martha both passed away at Truro on the same day—December 30, 1767—and were laid to rest in the old Presbyterian Cemetery.

Following his father’s passing, John Jr. assumed operation of his supply vessel. He married twice—first to Rachel Johnson, a marriage that resulted in the birth of three sons and two daughters, and then to Rachel (Duncan) Archibald, a union that produced one son. John Jr. made frequent trips to St. Marys, NS, where four of his sons—John, Samuel, Adam and William—eventually settled, along with his brother David and sister Margaret.

After his second wife’s passing, John Jr. moved to St. Marys, where he resided with his youngest son William until his passing. Born at Truro on September 13, 1857, William married Catherine Kirk, daughter of William and Catherine (McDonald) Kirk, Pictou, and established residence on “McKeen Hill,” Aspen, where the couple raised a family of 15 children.

One of William and Catherine’s children was a son, Samuel G. McKeen, born on May 26, 1825. Samuel G. married Margaret Taylor McKeen, daughter of Samuel and Margaret (Glencross) McKeen, in 1852. Samuel G. and Margaret’s son, Samuel Thomas, was born at Melrose around 1865. Samuel Thomas married Elizabeth “Eliza Bessie” Carthew and raised a family of three children—two sons, Clarence and William, and a daughter, Margaret “Alma.”

Alma McKeen married George Leibert Cameron in a ceremony held at East River St. Marys on October 27, 1916. The couple’s first child, Douglas Seaman, was born at Aspen the following year. A daughter, Olive Mildred, joined the household on February 14, 1919. At the time of the 1921 Canadian census, the family of four was living at Aspen, with Leibert’s occupation listed as “farmer.” His parents, Dougal and Margaret Cameron, resided next door.

Sometime shortly after 1921, the Cameron family relocated to Iroquois Falls, ON, where Leibert went to work for Abitibi Power and Paper Company. Established in 1914, its Iroquois Falls plant quickly became a major supplier of newsprint to the Canadian market. Three more children were born after the couple’s move to Iroquois Falls—sons George Bruce (YOB 1924) and John Leibert “Jack” (DOB May 31,1932) and a daughter Margaret (YOB 1933).

Douglas Seaman Cameron attended Iroquois Public School from 1924 to 1934 and went on to complete two years of studies at Iroquois Falls High School. Upon leaving school in 1936, he commenced employment at Abitibi Power and Paper, but left in 1938 because the “paper mill began running short time.”

Douglas then secured a job as a “diamond driller” [miner] with Pamour Gold Mines, Iroquois Falls, but left the position after 18 months because the “paper mill began to run full time.” During his employment underground with Pamour, Douglas was “hit on [the] left temple with [a] wrench.” The employment record in his service file provided further details:

“Knocked over but not unconscious. No headache or nausea following this. X-ray negative for fracture. Off work (underground) for four weeks but not confined to bed or house at all.”

In mid-1939, Douglas returned to work at Abitibi Power and Paper. In late September 1940, he submitted an application to the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), requesting a “flying duties” assignment. At the time, Douglas made reference to participating in a school cadets program, particularly pins that he earned “for shooting.”

On October 19, Douglas completed an interview at an RCAF Recruitment Centre at North Bay. The interviewer provided a brief assessment of his suitability for service: “Bright… seems very willing, should be o.k. after some training for air gunner.” Douglas returned to Iroquois Falls for several months before attesting with the RCAF at Hamilton, ON, on January 29, 1941, with an initial rank of Aircraftman Class II. Two days later, he departed for Brandon, MB, for basic training.

Douglas returned to Toronto, ON, in early March and remained there until April 20, when he was assigned to No. 5 Equipment Depot, Moncton, NB. He spent three months at the depot, awaiting orders to resume his courses.

On July 20, Douglas commenced wireless operator training at No. 1 Wireless School, Montreal, QC. After successfully completed the course, he was promoted to the rank of Leading Aircraftman on August 21. Douglas remained in Montreal throughout the autumn months, logging flying time and completing additional ground training courses. During that time, he placed 44th in a class of 139 recruits, with an overall grade of 81 %, and received authorization to wear a Wireless Operator’s badge.

On December 7, Douglas was “taken on strength” at No. 1 Bomber & Gunnery School, Jarvis, ON, for the final Canadian phase of his training. Over the next four weeks, he completed ground training courses, placing 32nd in a class of 50 cadets. Douglas also logged approximately 10 hours’ flying time, earning a grade of 77.7 % and placing 21st in his air training assessment. His performance warranted an “above average” rating. One instructor commented that he was “[a] hard worker, attentive at all times. Eager to make good.” Another described Douglas as “[a] popular man, reliable and trustworthy.”

Douglas earned his Air Gunner’s badge on January 3, 1942, and was promoted to the rank of Temporary Sergeant with pay. Three days later, he received two weeks’ embarkation leave and likely returned home for a visit. In mid-January, Douglas was attached to No. 3 Y Depot, Debert, NS, where he awaited orders to depart for overseas. He left Halifax on January 24, 1942, and arrived in the United Kingdom two weeks later.

On February 10, Douglas reported to No. 3 Personnel Centre, Bournemouth, UK. One month later, he “remustered” as a Wireless Operator/Air Gunner Class 2, and was assigned to No. 1 Signals School for further training on March 17, 1942. He then proceeded to No. 3 (O) Air Observers School on May 11, and commenced the final phase of his overseas training at No. 3 Radio School on June 10.

Having successfully completed the requirements for active duty, Douglas was promoted to the rank of Temporary Flight Sergeant on July 5. Following a 12-day leave at mid-month, he departed for No. 5 (C) Operational Training Unit (OTU), Turnberry, Scotland, on July 28.

OTUs provided RCAF personnel with their first opportunity to train aboard the aircraft in which they would serve. Air crews were also assembled at this stage, allowing the men to form a cohesive team during training before entering active service. Douglas’s crew mates were all Canadians—Pilot Sgt. Gilmar Innis Morrison, Vancouver, BC; Navigator Pilot Officer Thomas Harold O’Neil, Hamilton, ON; and Wireless Operator/Air Gunner Sgt. George Ernest Walker, Outremont, QC.

On September 22, 1942, the crew was assigned to a Torpedo Training Unit located at Abbotsinch, UK. One month later, the four men proceeded to 201 Group for active service. Formed in September 1939 from the Royal Air Force’s Middle East General Reconnaissance Group, the unit was responsible for coastal surveillance and provided vital information to strategic and tactical Allied units during the 1942 North African campaign.

On January 1, 1943, Douglas and his crew mates were attached to No. 39 Squadron, an active operating unit, for torpedo training. A regular bombing squadron at the time of the war’s outbreak, No. 39 Squadron was posted to the Mediterranean theatre in the spring of 1940 and transitioned to a maritime reconnaissance and anti-shipping role.

Following Italy’s entry into the war, No. 39’s aircraft conducted several bombing raids in Italian East Eritrea, after which its crews converted to operating Bristol Beaufort torpedo-bombers in August 1941. The Squadron’s personnel participated in anti-shipping operations for the remainder of the year and conducted their first torpedo attack on enemy shipping in late January 1942.

While No. 39 took part in a mid-June 1942 attack on the Italian battle fleet, its primary duties were mine-laying sorties and torpedo attacks on enemy shipping. Later that year, the Squadron provided support for Operation Torch—the allied invasion of North Africa. Briefly located in Egypt during the autumn and winter of 1942-43, the Squadron mainly operated out of the island of Malta until February 1943.

Two days after joining No. 39 Squadron—January 3, 1943—Douglas’s crew climbed aboard Beaufort DW 825 for a routine torpedo-training exercise in the Gulf of Suez, southwest of Cairo, Egypt, with HMS Arpha—a British naval vessel—playing the role of “target ship.” Documents in Douglas’s service file provide details on the subsequent events. A “Report on Flying Accident or Forced Landing Not Attributable to Enemy Action” states:

“This was the pilot’s first trip since completing a short torpedo course at Abbotsinch. He was detailed to complete two circuits and bumps prior to re-accustoming himself to flying low over the seas in the Low Flying Area. He was briefed not to fly dangerously low, not to attack the target or other shipping, and not to carry out any steep turns over the water.”

At approximately, 10:50 am, “a muffled explosion was heard and a Beaufort was observed about two miles from the ship flying close to the sea, and apparently in difficulties.” The aircraft plunged into the sea, prompting HMS Alpha and a nearby RAF launch to immediately proceed to the crash site. One crew member—Pilot Sgt. G I. Morrison—“was picked up alive, but badly injured. [Navigator] P/O O’Neil was picked up dead. The remaining two crew members [wireless operators/air gunners] were not located.” Sgt. Morrison was rushed to 13th General Hospital, where he succumbed to his injuries the following day.

The Report, dated the same day as the incident, proceeded to assess possible reasons why the aircraft struck the water:

“This may have been caused (1) by engine or other failure[,] but as the aircraft completed a satisfactory sortie prior to this sortie and was a most dependable aircraft, this is thought unlikely. (2) An error of judgement by the Pilot in that he completely misjudged his height or flew dangerously low, or (3) He failed to screw his throttles up and they slipped back[,] causing the aircraft to sink and hit the water.”

Wing Commander A. M. Taylor, who compiled the report, stated that he considered number two “the most likely reason” for the accident. Station Commander G. M. Knocker agreed, commenting:

“The pilot Sgt. Morrison came out to M. E. [The Mediterranean Expeditionary Force] by Sea and West Coast air route. Instructions have been given that in future pilots reporting straight to 5 METS [Meteorological Squadron] who have not flown aircraft out are to do at least two hours local flying before recommencing low flying [training] over the sea.”

Pilot Sgt. Morrison and Navigator Pilot Officer O’Neil were laid to rest in Suez War Memorial Cemetery, Suez, Egypt. The remains of the other two crew members—Wireless Operators/Air Gunners Sgt. George Ernest Walker and Douglas Seaman Cameron—were never recovered.

On October 29, 1943, Leibert Cameron received an official RCAF casualty notification telegram, informing him that his son Douglas, “previously reported ‘missing’ believed killed 3-Jan-43 as a result of a flying accident (overseas) (operations over the Gulf of Suez, Egypt) [is] now ‘presumed dead’ 3-Jan-43 for official purposes.” A subsequent letter from RCAF Records Officer T. K. McDougall, dated October 18, 1944, informed Leibert that Douglas has been posthumously promoted to the rank of Flight Sergeant, effective July 5, 1942.

Flight Sergeant Douglas Seaman Cameron’s name is engraved on the Alamein Memorial, located at the entrance to Alamein War Cemetery, Alamein, Egypt. The Land Forces panel contains the names of 8,500 military personnel who died in the Mediterranean theatre and have no known graves. The Air Forces panel displays the names of more than 3,000 Commonwealth airmen who died during Mediterranean operations and have no known final resting place.

Photograph of Flight Sergeant Douglas Seaman Cameron courtesy of Brenda (Cameron) & Pat Britton, Iroquois Falls, ON. Genealogical information on the McKeens of Aspen courtesy of Gerry & Melodie (McKeen) Madigan, Shubenacadie East, NS. Genealogical information on Douglas's Cameron ancestors courtesy of David Brown, Lochaber, NS.